|

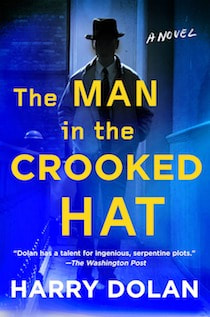

> Return to THE MAN IN THE CROOKED HAT main page

ORDER ONLINE Amazon Barnes & Noble IndieBound iBooks Books-A-Million Nicola's Books in Ann Arbor |

Excerpt from THE MAN IN THE CROOKED HATChapter 1 On the shore of the Huron River, Michael Underhill sits in the grass with his back against a tree. He watches the sunlight glinting on the water. He listens to the burble of the current. The woman is next to him, her back against the same tree. You could see them from the river, if you were out there in a canoe. But it’s late in the season. There’s no one on the water. Underhill picks up a leaf from the ground beside him. “Sometimes I think too much,” he says in a quiet voice. “I remember this thing that happened, an accident. Just dumb. I was driving to the grocery store on a Saturday afternoon, coming up to an intersection. I had the green light. There was a fire truck idling on the cross street. He had the red, so he was waiting. But he must have gotten a call, because suddenly he turned on his lights and siren.” The leaf is yellow and dry. Underhill twirls it by the stem. “Now I have to decide. Hit the brakes or go on through. It happened fast, but I remember thinking: This is not good. I hit the brakes. And I stopped in time, right at the intersection. But the car behind me didn’t. It slammed into me—I can still remember the sound. The driver was a kid. I think she was nineteen.” He holds the leaf steady and looks at the veins. “No one got hurt, and even the damage to my car wasn’t too bad. I had to take it in and have them replace the bumper and the tail-lights. The girl’s car was worse, but it wasn’t my problem. I wasn’t at fault. What the whole thing amounted to was a bad afternoon and some phone calls to the insurance company and a week of inconvenience while my car was in the shop. But I kept thinking about it. It didn’t have to happen. I could have made a different choice. When the driver of the fire truck turned on his siren, he didn’t move out into the intersection right away. I could have gone through and there would have been no harm. No damage. No hassle. So why didn’t I go through?” Underhill closes his hand around the leaf and feels it crumble. The woman is silent beside him. “It still bugs me, even though it happened years ago,” he says. “And this thing today, I know it’s going to be the same. I’m going to wonder if it might have turned out differently. If I had taken a different tack. If I had talked to you in a different place. It’ll bother me for a long time. In my defense, I think I handled it pretty well. I was friendly. You were friendly. We struck up a conversation. It’s broad daylight in a public park. You shouldn’t have been nervous. I didn’t think you were nervous. And I worked my way up to it—to asking you the question. It wasn’t a hard question. There’s no reason it should have made you suspicious. If you had given me a straight answer, that would have been the end of it. I would have smiled and gone away. No harm. All you had to do was tell me the truth.” He opens his hand and lets the pieces of the leaf fall to the ground. “But I could see that you weren’t comfortable,” he says. “You didn’t trust me. That wasn’t right. I didn’t deserve it. And then pretending you didn’t remember. That’s just clumsy. Anyone would have seen through that. What was I supposed to do? Let it go? How could I? By then we’d gone too far. You were starting to be afraid of me. You shouldn’t have been afraid of me.” Underhill gets up from the ground and brushes his hands over the front of his shirt. A cool wind touches his face. The woman doesn’t stir. Out in the river, a fish breaks the surface of the water. “You shouldn’t have been afraid of me,” Underhill says again. The woman’s camera is lying in the grass where it fell. Underhill lifts it by the strap, swings it back and forth to build momentum, and hurls it out into the middle of the river. He returns to the tree and crouches down. He touches a lock of hair that has fallen over the woman’s forehead. He takes her ear-rings from her ears, takes her wedding band. Throws them out into the water. They don’t go as far, but it’s far enough. He stands on the shore, wondering if there’s anything else he should do. “This is as much on you as it is on me,” he says after a while. “I’m not going to feel bad about this.” One last look around. His hat is in the grass. He picks it up and puts it on his head and walks away. Chapter 2 Eighteen months later If you wandered through midtown Detroit that spring, you saw the flyers. You saw them if you went to the Shinola store on Canfield Street, or Third Man Records, or any sort of hipster hangout. One on every stretch of bare brick wall. You saw them on the campus of Wayne State University and at each entrance to the Public Library. You saw them in front of the DIA—the Detroit Institute of Arts—taped to the granite base of Rodin’s Thinker. At least until the maintenance workers came to peel them off. They were sheets of white paper, eight and a half by eleven, printed with a composite sketch of a man’s face—a man wearing a fedora. There were two lines of type above the sketch. The first asked: have you seen him? The second was an email address. You may have spotted the person who put them up. He would have been carrying a sheaf of them under his arm, and a roll of white duct tape. You might have wondered about him. He wore good clothes, but sometimes he wore them carelessly. One sleeve rolled up and one left down. Shirt-tails untucked. His hygiene left no room for complaint, but his shaving was haphazard. He moved at his own pace, half a step slower than everyone around him. If you got close enough to see his eyes, you might have suspected he wasn’t getting enough sleep. If you tried to engage him in conversation, it would have been hit or miss. He could be friendly, but he might not have patience for small talk. He was a difficult person to get to know. His name was Jack Pellum. # That Tuesday, Jack had one important thing to do, and two unimportant things. The first unimportant thing was an appointment with Dr. Eleanor Brannon at her office on Selden Street. He arrived twenty minutes late. Dr. Brannon heard his knock and greeted him at the door. She offered him one of the two chairs in the room and took the other. The low table between them held a box of tissues and a vase of spring flowers. Jack moved the vase aside to make room for his stack of flyers. The duct tape went on top. There were pleasantries. Wasn’t it a fine sunny afternoon? It was. Did Jack have any trouble finding the office? None at all. Dr. Brannon opened a file in her lap and put on a pair of reading glasses. “You were seeing Dr. Kershaw,” she said. “Yes.” “And it turned out the two of you had different styles of communication.” Jack settled back in his chair. “Is that what he told you?” “Not in so many words. He said you threatened him.” Dr. Brannon’s voice was mild. Unconcerned. “Really?” Jack said. “You told him—” She consulted the file. “You told him you wanted to rip out his heart and eat it. . . . That’s quite colorful.” “It’s not true.” “No?” “I said I wanted to cut out his heart and fry it in a pan. I never said anything about eating it.” Dr. Brannon may have wanted to smile. Jack couldn’t be sure. If she did, she resisted. “And you weren’t making a threat,” she said. “I was trying to make a point. He kept telling me that his office was a safe place. I could say anything I wanted there, without fear of being judged.” Jack paused, tapping the arm of the chair. “I don’t think he understood me.” Dr. Brannon turned a page in the file. “So, as I said, you had different styles of communication. Why did you go to him originally?” “My father thought I would benefit from talking to someone.” “You’re thirty-five years old.” “Yes.” “So you’re not bound by your father’s wishes.” “No, but I have reasons to take his wishes into account.” “What reasons?” “He’s paying my rent, for one thing.” Dr. Brannon looked up at Jack. “You don’t have money of your own? You’re not working?” “Not for a while.” “I understand you used to be a police officer.” “I was a detective.” “But not anymore.” “I quit. The year before last.” “Why?” “You know why,” Jack said. “It’s in the file.” “I’d like to hear it from you.” Sometimes Jack’s hands make themselves into fists without his realizing. He opened them now and flexed his fingers. “My wife died,” he said. “Olivia.” “Yes, Olivia.” “She was murdered.” “She was strangled on an afternoon in October,” Jack said, “and left propped against a tree by the shore of the Huron River.” “I’m sorry,” said Dr. Brannon. Jack never knew how to respond to condolences. He kept quiet. “And after that,” the doctor said, “you didn’t want to be a detective anymore.” “After that, I desperately wanted to be a detective. But the only case I cared about was hers, and no one would let me anywhere near it. My lieutenant told me to take some time off.” “And you haven’t gone back.” “I can’t see the point.” “It might do you good, to be working. Some people find that work helps them cope with grief.” Jack flexed his fingers again. “Is that where we are now? You’re going to ask me how I’m coping?” “Does that word bother you?” “I don’t care about the word.” “Do you think you’re dealing well with your wife’s death?” “Should I be honest?” “Please.” “I don’t think that’s any of your goddamn business.” The profanity left the doctor unfazed. She turned some more pages. “Yet you’re here,” she said. “Do you want to tell me about George Hanley?” “Jesus, is that in the file?” “You were arrested for assaulting him two months ago. You broke his nose.” “That’s not entirely accurate.” “Which part?” “I wasn’t arrested.” “Why don’t you tell me what happened.” Jack leaned forward, let out a long breath. “Look, that was a mistake. I wasn’t thinking clearly. You have to understand, when you’re investigating a homicide, sometimes there’s very little to go on. And then maybe you start reaching. For anything. Olivia was a photographer. A freelancer. One of the things she did, she worked for Ford, photographing cars for their brochures. That’s a good job. It pays well. After she died, George Hanley got hired to replace her. So in a sense, he benefited from her death. That gave him a motive.” “Did Mr. Hanley have a criminal record?” “No.” “But you thought he might have killed your wife to pick up some freelance work.” “I just wanted to talk to him,” Jack said. “I’m afraid I didn’t come across very well. He didn’t like the tone of my questions. He got angry. We both did.” “You hit him.” “It went further than I intended.” “But you weren’t arrested.” “No.” Dr. Brannon took off her reading glasses. “Even though you shouldn’t have been questioning him in the first place. You had no authority. And you caused him grave physical harm.” “I don’t know how grave it was.” “He didn’t call the police?” “Oh, he called them, and they came,” Jack said. “They put me in the back of a squad car and drove me away. If you want to call that an arrest. Nothing happened to me. From what I heard, Hanley wanted to press charges at first, and then later on he didn’t.” “What made him change his mind?” “I imagine someone talked to him. You know who my father is, right?” Dr. Brannon nodded. “He’s a judge.” “He’s a federal judge on the sixth district court of appeals.” She raised an eyebrow. “So you’re saying he made the assault charge go away.” “I’m pretty sure he made the assault itself go away. If you went looking, I think you’d find that there’s not a scrap of documentation. No incident report, no witness statements. It never happened. I’m surprised he didn’t send someone to scrub it from that file.” Dr. Brannon balanced her glasses on the arm of her chair. She smoothed her hair from her forehead. It was dark but turning silver. She was probably ten years older than Jack. Short, slender, well-dressed in a silk blouse and a navy blue skirt. She seemed calm and benevolent and Jack wanted to like her. She said, “Do you think your father is looking out for your best interests?” “I’m not here to talk about my father.” “Yet he’s come up twice now. Tell me about him.” “He’s not an easy man to explain.” “Tell me the first thing that comes to mind.” “He used to play catch with me when I was a kid.” She smiled. “Tell me the second thing that comes to mind.” Jack hesitated. Studied the flowers on the table between them. Finally he looked up and met her eyes. “This past Christmas, my father wanted to know about my plans for the future. I said I was thinking about going back to school, to study law.” “All right.” “Then about six weeks ago, I got an acceptance letter from the law school of the University of Michigan. They’re holding a place for me there in the fall.” “Congratulations.” “You’re not following me,” Jack said. “I didn’t apply. I wasn’t that serious about it. My father made it happen. He took care of it, like he took care of the assault. That’s only the beginning. Last week I got my private investigator’s license.” The doctor tipped her head to the side. “You didn’t apply for that either?” “I didn’t have to. It came in the mail—because a while back I happened to mention that it was an option I was considering, becoming a P.I. I got business cards last week too: Jack Pellum Investigations. They showed up on my doorstep. I’ve already been getting calls from potential clients. Apparently I advertise online. If you Google Detroit private investigators, my name comes up first.” Dr. Brannon looked thoughtful for a moment. “It sounds like your father wants to help you. I’m not saying he’s going about it in the right way. But it sounds like his intentions are good. Would you agree?” “Probably.” “What do you think he wants for you?” “He says he wants me to be happy.” “You sound skeptical.” “I think he’d take happy if he could get it. Otherwise he’d settle for normal.” “What do you want?” “That’s a large question.” “Yes.” “And again I’m not sure if it’s any of your business.” It seemed to Jack that Dr. Brannon wanted to sigh. But she managed to hold it in. “All right,” she said. “What do you want from me?” He let a few seconds pass, making up his mind. “I might like to come here and talk to you. Occasionally.” “For what purpose?” “To keep my father off my back.” “You could get the same result by pretending to come here,” she said. “What would we talk about?” “It doesn’t really matter.” “Would we talk about Olivia?” “Possibly.” “I don’t know if I can help you.” “I don’t expect you to.” Dr. Brannon closed the file, and her eyes turned sad and kind. “Your wife died, for no good reason,” she said. “People die and leave us behind and we have to find a way to go on. You’re coming up against the human condition, Mr. Pellum. You could meet with me and talk about her and it might make you feel better. Or it might not.” “It doesn’t matter,” Jack said. # After he left Dr. Brannon’s office, Jack made his way up Woodward Avenue. The temperature stood in the sixties, but he had the sidewalk mostly to himself. He put up some flyers at the Majestic Theater and crossed the street to tape one to the gate of the Whitney House. He knew from experience it wouldn’t stay there long, but you do what you can. His walk ended at the DIA—the site of the second unimportant thing he had to do that afternoon. He sat on the steps in front of the museum and waited. School kids milled around nearby. Two of them had rolled-up posters from the gift shop. They fought a duel up and down the steps, using the posters as swords, until a sour-faced teacher came by and told them to knock it off. Around then a schoolbus drove up to the curb and the kids started getting on, and Jack looked across the street and saw a woman watching him uncertainly. He gave her a little wave to encourage her. She waited for a gap in traffic and crossed over to his side. Her clothes were upscale casual: cashmere sweater, black jeans, designer handbag, leather boots. She wore her blond hair in a ponytail. Jack put her age in the mid-thirties. He rose as she came up the steps. “Mr. Pellum?” she said. “I’m Kim Weaver.” Jack gave her a smile. Low-grade, professional. “Nice to meet you.” She put out a hand and he took it briefly and they stalled after that. She looked around, taking in the steps and the pillars at the entrance of the museum. “We could go inside,” Jack said. “But I thought we might talk here.” The last of the school kids went down to the bus, leaving them alone, and Kim Weaver made her decision. “Here is fine.” They sat on the steps, with Jack’s leftover flyers between them. “I’ve never done this before,” Kim said. “Hired a detective.” “I’m new to it myself,” Jack told her. “I wouldn’t have known who to call. But then I saw your billboard.” “My billboard?” “The one on the interstate, near the airport.” “Oh that one. Sure.” “And now here we are. You’re not what I expected.” “I’m not?” “I thought you’d be older and, I don’t know, smelling of cigar smoke.” Jack gave her the smile again. They watched the school bus ease away from the curb and roll up Woodward. When it was out of sight Kim got to her point. “It’s my husband,” she said. “I think he’s having an affair.” “Okay.” “It’s such a cliché. You must hear it all the time.” “What’s his name?” “Doug.” “What makes you think he’s having an affair?” “A few things. Lately he’s been working more. Or he says he has.” “What does he do?” “He sells real estate. The past few months, he’s been spending more time at it. But he’s not making more sales. Sometimes he works until ten or eleven at night. I know he’s not showing houses that late. He says he’s doing paperwork, but if I drive by his office he’s not there. Then there’s his phone. He started locking it, so you have to key in a number—” “A passcode,” Jack said. “Right. He never did that before. It makes me think he’s keeping secrets. And then there’s a woman, Gwen Davis, another agent. She started working at his company last year, and she’s the type he would go for. I’ve seen the way he acts around her. There’s something going on. I’m not blind.” “Have you asked him about it?” “He denies it. Says I’m being paranoid.” “What about the phone?” “He says the passcode is for safety, in case it gets stolen. Which sounds reasonable, right?” “Sure.” “So I put a lock on my phone too. And I gave him the code, in case he needed it. Like in an emergency. But he wouldn’t give me his code. He said he wouldn’t play that game. He said I should trust him. You’re married, aren’t you?” The question caught Jack by surprise. He wondered for a moment why she would make that assumption, but the answer was obvious. He looked down at his left hand. He still wore the ring. “I used to be,” he said. Kim Weaver turned away, embarrassed. “I don’t mean to be nosy. I’ve been married for five years, but Doug and I knew each other for another three before. I didn’t want to rush into it. I took it seriously. I wanted to be sure. It’s not the way I thought it would be. I don’t like it, feeling this way. Like it was a mistake.” She went quiet and they sat together watching the traffic on Woodward. An elderly couple came out of the museum behind them and made a slow descent down the steps. Jack thought about Dr. Brannon and the question she had asked him. “What do you want?” he said. Kim Weaver pulled the sleeves of her sweater down over her hands, as if the day had turned cold. “I want to live a good life,” she said. “I want the world to be fair. I want a husband I don’t have to doubt. I want to feel like I made the right choices.” “What do you want from me?” She bent forward, resting her elbows on her thighs. “I guess I want you to follow Doug around and see if he’s sleeping with Gwen Davis. I want you to see if they’re doing it at her apartment or in a hotel or in some empty house with a ‘For Sale’ sign in front of it. I want you to get up close and look through the window and maybe take pictures, because if I don’t have proof he’ll keep denying it, and I don’t think I could stand it, going on this way.” Jack nodded. “I’ll do that for you, if you’re certain it’s what you want.” “Will you?” “Absolutely. I’ll skulk around, and I’ll take pictures. But you have to be certain.” “You don’t think it’s a good idea.” “I won’t say one way or the other. But there are things you might want to take into account.” “Such as?” “His dignity. And yours. And mine. I don’t care so much about mine, but it’s something to consider. It’s part of the mix. Let me ask you this: What would you do if you found out you were right, if I got you proof that he was cheating?” “I’d leave him. Divorce him.” “You could do that now.” “But shouldn’t I be sure?” Jack shrugged. “You sound like you are. I’m pretty sure, just from what you’ve said. And I’m not the one living with him. But forget about cheating. Leave it aside. Is he treating you the way you want to be treated? Is he acting like he cares about you?” “No. He’s distant, and cold.” “So why stay with him? Do you have children?” “No.” “Then it’s easy. Do what you want.” Kim searched for a response to that, and didn’t find one. Jack shifted his feet to a lower step, stretching his legs. Down on the street, a silver Town Car drifted by slowly. Beside him, Kim’s hands came out of the sleeves of her sweater and dug through her handbag for a tissue. She wiped away some tears. Not many, not in front of a stranger. Jack wanted to reach over and pat her shoulder. He didn’t. The tissue went back into her bag. Kim sniffed and started to get up and then noticed the flyers lying on the step. She tugged one of them out from underneath the roll of duct tape. “Who’s this?” she asked. “A missing person?” “Sort of,” Jack said. “He’s someone I need to talk to.” Kim let herself smile. “You must handle a lot of missing person cases.” “Why do you say that?” “You’re not making any money off of wives with cheating husbands.” She tapped the flyer. “What’s his story, the man in the hat?” “I don’t know. Does he look familiar?” “I can’t say he does.” “All right.” “But at the same time, I feel like I’ve seen him before. You know what I mean?” “Yes.” “There’s not much to him. He could be nobody. Or anybody. I might have passed him twice on the street today. But if I saw him again tomorrow, I might not remember. Does that make sense?” “It does.” She returned the flyer to the stack. “I hope you find him,” she said. She stood, and Jack did too. “I’m glad we had this talk,” she said, adjusting the strap of her handbag on her shoulder. “But then again, I’m not glad about it at all.” “I know.” She thanked him and said goodbye and turned away. Jack watched her walk down the steps and head off at a crisp pace along Woodward. He was still watching her when the silver Town Car came by again. He figured it must have circled the block. It stopped and let out a passenger from the back seat before driving on. The passenger was tall and rail thin and wore a tailored black suit. He had gray hair and a stern, grim face. If you were casting him in a film, he might play a scarecrow or the angel of death. He was Alton Pellum, Jack’s father. Jack sat down again and waited. His father approached him, but not directly. He went to the statue of Rodin’s Thinker first and casually tore the flyers from the base. He wadded up the tape and crumpled the paper and stuffed everything in the pockets of his jacket. When he reached Jack, he eased himself down on the step beside him. “Lovely woman, the blonde,” he said. “Is she someone you’re seeing, or is that too much to hope?” “It’s strictly professional,” Jack said. “She had a job she needed help with.” “I trust you took it.” “I already helped her. What brings you here?” Alton Pellum clasped his hands together over one knee. “I come here quite often,” he said. “I go around the neighborhood and count your little posters. It’s the only way I have of assessing your well-being.” “It can’t be the only way.” “What’s another?” “You could ask me how I am.” “Very well. How are you, Jack?” “I’m fine.” Jack’s father frowned. “That’s uninformative, and probably a lie. Have you gone to see that new doctor?” “I saw her today.” “And?” “She’s good. Better than the last one. I think she’s someone I could talk to.” Jack watched the knuckles of his father’s hands turn white. Alton Pellum said, “Why do I think you’re telling me what I want to hear?” “Would you rather I told you things you didn’t want to hear?” “Yes, if they were true.” “Then I will endeavor to tell you only true things from now on.” “That would be a welcome change. We worry about you, your mother and I.” “I don’t want you to worry.” “Nonetheless, we do,” Alton Pellum said. “Have you been getting enough sleep?” “More or less.” “Have you been exercising?” “Yes.” “Have you been eating properly?” “Yes.” “Your mother would like you to come for dinner.” “Yes.” “So you’ll come?” “No. I was acknowledging that she would like me to come.” “Don’t be a smart aleck. She’d like to fix you a home-cooked meal. Perhaps roast pork or lamb.” “Her lamb is terrible,” Jack said. “That’s an exaggeration. It’s also irrelevant.” “She made it for Christmas and I could barely chew it,” Jack said. “I ate it anyway and it sat in my stomach for three days. I would rather she shaved the wool off a lamb and fed me that.” “She doesn’t have to make lamb.” “Whatever she makes will be heavy and bland. She’s not a good cook.” “We’ll go to a restaurant then. The main thing is, she’d like to talk to you.” “She’s not a good conversationalist either.” “Now you’re being flippant,” Jack’s father said. “I don’t think you realize how hurt your mother would be if she heard you saying these things.” “I do realize. I just don’t care that much about hurting her feelings. Or yours.” Anger turned Alton Pellum’s grim face grimmer and he got up on his feet. Jack picked up the tape and the flyers and did the same. His father’s breath rumbled in his throat and the old man’s dark eyes glared. “That’s fine, Jack,” he said softly. “You have chastened me with your truth-telling. I am defeated. Your mother would still like to see you. We will keep her innocent of your true nature. You’ll have to pretend you’re a good son and find something to say to her. Can you do that?” “I could,” Jack said, “but it would be an effort.” “We’ll make it as painless as possible. We’ll meet at a restaurant of your choosing. We could do it tonight, get it over with. Then you could go on about your life.” “Tonight’s no good.” “Some other night then. But soon.” Alton Pellum started down the steps without another word, his back straight, his head held high. Jack followed him. The silver Town Car was waiting when they got to the street. Jack held the door while his father climbed in. Jack shut the door but the car didn’t move. The window came down and his father leaned toward him, his anger gone, replaced with weariness. “Are you sure you can’t make it tonight?” the old man said. “It would mean a great deal to your mother. To both of us.” “I’m sorry, Dad. I really can’t. I’ve got something important to do.” Chapter 3 The Park Bar in downtown Detroit attracts twenty-somethings who work nearby and people going to shows at the Fox Theatre and the Fillmore. It’s a big room with a square bar in the middle and booths along each wall. It’s moderately crowded even at six on a Tuesday night. Jack Pellum bought a Coke at the bar, claimed a booth, and used his phone to check his email. There were a handful of new messages to the address on the flyers: [email protected]. The first one was typical: Have I seen him? Yeah I saw him in an alley once, fucking your sister.The others were equally useful: Is that Jimmy Hoffa? they said, or Have you found Jesus? or Stop taping your shit to my wall, asshole. He deleted them one by one. Around quarter after six Jack heard a voice he recognized calling out to one of the bartenders for a beer. He looked up and saw Carl Dumisani, all six feet of him, broad-shouldered, bulging a little at the stomach, but solid. He wore a blue suit, the jacket folded over his arm. White shirt and suspenders. Loose tie. He dropped some bills on the bar and picked up his mug and carried it over. Eased himself into the booth across from Jack. He took a slow drink and looked Jack over. Carl had gentle brown eyes and skin the color of caramel. Jack had spent a lot of time with him once. It was Carl who had trained Jack when he became a detective. They rode together for five years before Jack quit. Carl Dumisani put his mug down and said, “We’re back to the flyers again, Pellum?” They were on the table next to Jack’s phone. “I guess we are,” he said. “Thought you were gonna stop.” “I did. Held out for about three weeks.” “I guess that’s better than some people do.” Carl reached over and took one from the top of the stack. “Honest to god, you might as well put up a sign that says, You ever seen a white man in a hat? See if that works.” “There’s an idea.” “Seriously, you ever get anything off these?” “Not yet.” “Maybe that’s ’cause there’s nothing to get.” Carl put the flyer back. “This can’t go on, Pellum.” “Don’t try to fix me, Carl.” “I wouldn’t. You’re my boy, you know that. Even when you’re broken. But it’s not up to me.” He had a deep voice, and Jack could hear the regret in it. “You go on as long as you want,” Carl said. “I won’t stop you. But you and me, meeting like this, it has to end. The word has come down.” “From who?” “From the lieutenant, and she got the word from the chief, and I don’t know where he got the word but I can guess. Probably from a man wears a black robe.” Sometimes Jack gets a sick feeling, a tightness in his chest, like he’s breathing air but there’s not enough oxygen in it. But it always passes. If he holds out, he can make it pass. “Okay,” Jack said. “We can deal with this. We’ve been careless, meeting at the same time every week, in the same place. Someone was bound to notice. We can change things up.” “No. You’re not hearing me. It’s done.” “I know it’s a risk for you—” “And I’d take the risk, you know I would, if I thought it was doing you any good. But it’s not.” “I can talk to my father—” Carl Dumisani reached over and touched Jack’s arm with his thick fingers. Jack had seen him do it before, to people they interrogated. It was meant to soothe them. “We’re not bargaining, kid,” Carl said. “This is the last time. You want to do this or not?” Jack didn’t answer. He was dealing with the thing that was pushing down on his chest. He worked on controlling his breathing. He told himself he wasn’t in danger. He wasn’t going to die. It only felt that way. “We don’t have to do this,” Carl said. “You know that, right? You can come back. I’ll put in a word for you. Not that it’ll matter. The only thing that’ll matter is your father, and we both know he’s got the juice to get you back in. You and me can partner up again. I’d be happy to. You should see the clown they put me with.” He meant it. Jack knew. But it didn’t matter. The offer didn’t tempt him. Jack waved it away. And the other thing, the feeling in his chest, it passed. “This is the last time,” he said. “I understand. Let’s do it.” Carl drank from his mug, watching Jack over the rim. Jack could see his disappointment. “Okay,” Carl said. “There were four new homicides in the city this past week, and one in Dearborn.” He pulled a small notebook from his pocket and consulted it. “The Dearborn one is easy. Guy got into a fight with his brother in law, beat him with a wrench. Called 911 himself and confessed. Safe to say, the man in the hat was not involved.” Jack nodded his agreement. “I read about that one in the Free Press.” “Now, the other four,” Carl said. “Two of them were gang-related. Both victims were young men. Nineteen and twenty-three. Both had priors for drug offenses. Both were shot. One black. One Hispanic. We don’t have any suspects yet, no one’s talking, but it doesn’t sound like the man in the hat to me.” Carl waited to see if Jack would contradict him. When it didn’t happen, he continued. “The next one is a black female victim in her thirties. Tamika LaSalle. Her body was found in an abandoned house on Eight Mile. It had been there a few days.” “I read about that one too,” Jack said. “I figured you would. Now there’s a superficial similarity with Olivia’s case, in that Tamika LaSalle was strangled, but that’s where it ends. LaSalle’s killer used a ligature—an extension cord. We found it wrapped around her neck. Her body was hidden in a closet, not left out in the open. Different MOs. The other difference: LaSalle had a history of arrests for prostitution. She had a pimp: a man named Jamal Hudlin. He’s the one we’re focusing on. I think he did it. A friend of the victim says she wanted to leave him. And he has a temper. He’s done time for assault before. But if there’s any reason to connect him with Olivia’s death, I can’t see it. Do you think I’m wrong?” Jack thought it over, longer than he had to. “You’re not wrong,” he said. “What about the last one?” Carl took another drink of beer, brought the mug down to the table, flicked his fingers against the handle. “The last one’s weird,” he said. “I don’t even want to tell you about it.” “Come on, Carl.” “I’m afraid you’re gonna cling to it and waste your time obsessing over it. But it’s really nothing. It’s a suicide.” “I haven’t read about any suicide.” Carl resigned himself, looked down at his notebook. “Happened on Friday in Corktown. Didn’t make the papers. White male, thirty-three years old. Daniel Cavanaugh. He was living alone. Distraught over the death of his wife. She had one of those awful kinds of cancer that kill you young. Leukemia, I think. He cut open the ceiling in his living room and tied a rope around a wooden beam and hanged himself. A neighbor found him.” “That’s a shame,” Jack said, “but why would I obsess about it? Is there something you’re leaving out? Did he look like the man in the hat?” Carl smiled faintly at the idea. “I don’t think so. Not particularly.” “Then what’s special about this case? Could it have been staged? Is there any doubt it was a suicide?” Carl shook his head. “Everyone agrees Cavanaugh was depressed. And he had tried it once before, with pills.” “Did he leave a note?” Carl fiddled some more with the handle of his mug. “That’s the thing that’s a little strange. He left two. He painted them on the walls of his living room, in letters a foot high. He was a writer. I guess he had a flair for the dramatic. One of them said, What’s so great about any of this? Sort of an all-purpose sentiment if you’re gonna kill yourself.” “What did the other one say?” Carl sighed. “The other one is the one you’re gonna get worked up about. But I swear to you, I don’t think it means anything. It’s just a coincidence.” “What did it say?” Carl lifted his broad shoulders, let them fall again. “It said, There’s a killer, and he wears a crooked hat.” (End of excerpt) Order THE MAN IN THE CROOKED HAT online: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound | iBooks |Books-A-Million |